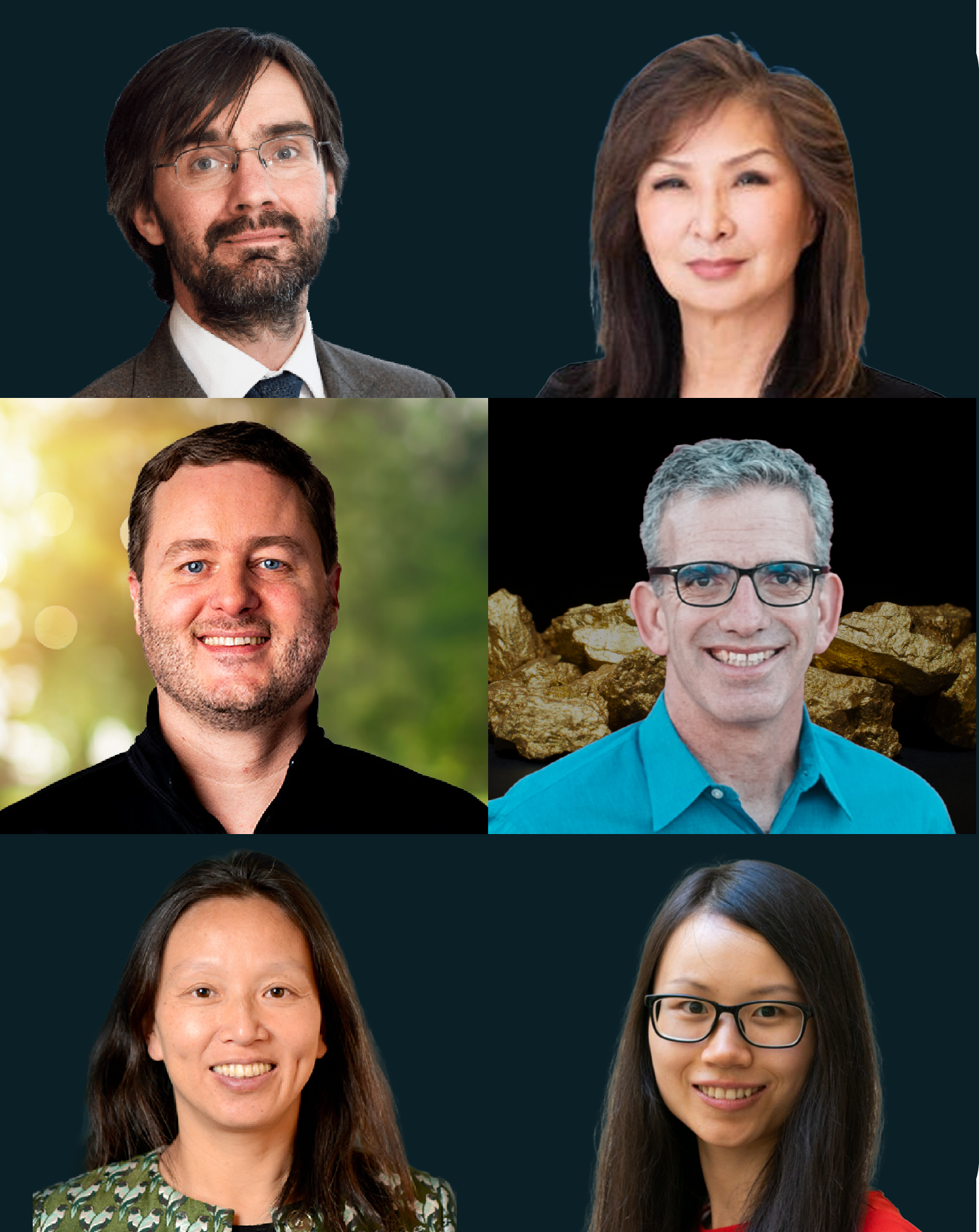

Corporate Venturing Insider spotlights voices across corporate venture to surface practical ways corporates can support entrepreneurs. Last issue, InMotion Ventures’ Mike Smeed turned his interview into a stealth promo for GCV—so we invited GCV back on. In episode #111, Nicolas Sauvage spoke with Tammi Smorynski, a 24-year Intel Capital veteran now teaching board-readiness at the GCV Institute. She pairs operating depth with a teacher’s clarity on boardcraft, down-cycle discipline, the false choice of “strategic versus financial,” and learning fast from misses.

Smorynski’s path is grounded: accountant, J.P. Morgan audit, investment banking, then an MBA from UCLA. In the unusual 1999–2001 window Intel ran a rare MBA hiring program during the dot-com bust; she joined via treasury when Intel Capital still used a cumbersome “three-legged stool” of strategic investment managers, treasury, and legal. By 2000 the group was fully branded and—by CVC standards—massive, becoming the gold standard for CVCs. Over time the mandate shifted to fewer companies, larger checks, and more board seats. That breadth across treasury, investing, and portfolio work shaped a durable view: “the pendulum swings, but CVCs always be strategic or risk getting cut”.

Other than joining during a historic period, Smorynski learned different muscles from successive leaders. Founder Les Vadasz (Intel employee No.3) modeled calm in crisis during the dot-com bust: “Steady as she goes. Don’t panic.” Arvind Sodhani, a mentor of Tammi’s, merged treasury and investing and embedded Intel Capital in business units, proving diversification across sectors and geographies cushions cycles and that deep BU integration sharpens diligence and follow-through. Wendell Brooks leaned into fewer, larger, higher-conviction bets with board seats and quite literally walked the floor. Anthony Lin, the latest in this line of managers, brought a collaborative, accessible style and realism about tough markets; by then Smorynski says it was easier to speak her mind, and he welcomed it. The through-line is simple: like Intel Capital in its nearly 25 year run, great CVCs are living systems that adjust team size, geographic footprint, and board posture with the market while staying close to the corporate mothership. Intel Capital leaders have long sat near the CEO; proximity and alignment matter.

When it comes to her own style, Smorynski’s most transferable habit is radical transparency with the investment committee. “I once opened with, ‘I cannot justify this valuation.’ No comps, no perfect metric—then I laid out why the expected value still worked and where the asymmetric upside was. They approved it.” Committees don’t need theatrics; they need risks, upside, and trade-offs presented plainly so everyone proceeds eyes-open. Preempt the hardest objection first; surprises break trust more than losses.

She is equally blunt about failure: treat zeros as tuition. “My first deal cratered. I took it personally—‘we’re losing a million dollars’—and almost broke down. A manager told me: ‘That’s venture, Tammi.’” Now she reframes losses as learning: “That was your $1M training” Nicolas added.

On cycles, she has pattern recognition from those failtures—dot-com, 2008, SPAC whiplash, COVID, SVB—yet says 2025 feels “weird”. Markets look strong, but the correction question lingers. She’s cautiously optimistic on deep tech and hardware: after years out of favor, leaders like NVIDIA, SpaceX, and Tesla show hardware can command outsized value and pull more engineers to found. Still, avoid stampedes: “Right after dot-com came the optical bubble. When everyone runs in the same direction, that doesn’t mean you should.” Diversify by sector and stage; cycles rotate and discipline compounds.

For board work, the topic of her upcoming class, she offers a practical tool: an eight-slide handover pack to inherit a company or get board-ready fast. It is not a pitch deck; it’s an operator’s cheat sheet. Capture a crisp company snapshot when you inherit an investment, document your firm’s position, include a clean cap table and a board map with follow-on capacity, summarize key terms and any special rights, note the areas of strategic engagement with the corporate, and flag special situations such as fundraising, M&A interest, runway, and near-term catalysts. If the story is tangled, draw it. Two anchors: know other investors’ dry powder, and in cram-downs check both protective provisions and mandatory conversion.

On whether to take a board seat or observe, Smorynski says it depends. Corporates must weigh accounting risk, customer or supplier conflicts, and whether they will invest across competitive spaces. A strong observer with credibility and relationships can achieve most of the impact with fewer constraints. A tell of a healthy board is that “You can’t tell who votes and who observes until the minutes are approved.”

After 24 years, Smorynski wanted to keep contributing without the constant fire drill. Her GCVI Institute course is the pragmatic two-day playbook she wished she’d had, with new modules coming on term sheets, cap tables, and waterfalls. Outside venture, she is a substitute teacher at a local high school. If you or your team sit on—or around—startup boards, her GCVI courses are worth it: a practitioner’s curriculum of checklists, slide templates, term-sheet landmines, and tactics for hairy financings. Two TDK Ventures team members attended and, in Nicolas’s words, were “raving about it.”

_________________________________________________________________________

Enjoyed this conversation?

Discover more insights from corporate innovators, top investors, and founders at cv-insider.com—the official home of the Corporate Venturing Insider series.

Follow us on your favorite platform for bite-sized takeaways and full episodes from across the CVC ecosystem:

Apple Podcasts

Spotify

✍️ Medium

In all cycles, “steady as she goes”—be calm, disciplined, and present for your founders.

In all cycles, “steady as she goes”—be calm, disciplined, and present for your founders.